Accessing employment records in the private sector: Navigating the intersection of privacy and workplace Law

16 Nov 2025

The question of whether an individual can access their personal information from their current or former employer sits at the intersection of primarily two overlapping regulatory regimes:

- the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) (Privacy Act) and

- the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (Fair Work Act).

While employees often assume they have a general right to see all information their employer holds about them, the reality is more complex.

The scope of access rights depends on the type of information, the statutory framework under which it is held, and the balance that has struck between workplace relations regulation and data protection. Understanding the difference is critical, because an access request that fails under one regime may succeed under the other.

This article is part one of a two-part series and focuses exclusively on access rights under the Privacy Act. Part two (coming soon) will turn to access rights under the Fair Work Act. Taken together, the series will provide a practical framework for responding to access requests made by employees, ex-employees or job applicants.

Setting the scene: who does the Privacy Act apply to?

Before considering information access rights, it is necessary to pause and ask a threshold question: does the Privacy Act apply to the entity holding the information? The Privacy Act regulates the handling of personal information by both public and private sector entities in Australia, specifically:

- Australian Government agencies (including federal government departments, statutory agencies and bodies).[1]

- Private sector organisations with an annual turnover of more than $3 million (including companies, incorporated associations, partnerships, trusts and sole traders).[2]

- Certain small businesses with a turnover under $3 million, if they fall into a prescribed category, such as:

- health service providers (including medical practitioners, allied health professionals, gyms and childcare centres);

- businesses that trade in personal information;

- credit reporting bodies;

- entities that hold tax file number information;

- reporting entities for the purpose of the Anti-Money Laundering and Counter-Terrorism Financing Act (2006);

- contractors providing services to the Commonwealth.[3]

Importantly, the Privacy Act generally does not extend to state or territory government agencies unless an exception applies. In Western Australia, state agencies will soon be covered by the Privacy and Responsible Information Sharing Act 2024 (WA) (PRIS Act). The PRIS Act has equivalent information access mechanisms for the Western Australian government agencies it applies to, but these will not be covered in this article. Some other states and territories also have their own privacy regimes.

Access rights under the Privacy Act

The Privacy Act gives individuals a right to request access to their personal information under Australian Privacy Principle (APP) 12.

‘Personal information’ is information or an opinion about an identified individual, or an individual who is reasonably identifiable:

- whether the information or opinion is true or not, and

- whether the information or opinion is recorded in a material form or not.

However, the Privacy Act carves out an exemption to access for private sector employers in relation to “employee records” where those records are directly related to the employment relationship.[4] That is, a private‑sector employer’s handling of employee records is exempt from the APPs (e.g. right to request access) if:

- the act or practice is directly related to a current or former employment relationship; and

- relates to an employee record held by the employer.

Employee records are defined broadly - covering personal information such as health details, terms and conditions of employment, performance conduct, leave, and remuneration.[5]

This means that requests by current or former employees for access to such information cannot be compelled under the Privacy Act. This was the original intention of the Australian Parliament when it expanded the Privacy Act’s coverage to private sector organisations in 2000:

“The Government has agreed that the handling of employee records is a matter better dealt with under workplace relations legislation.”[6]

So how does this work in practice?

By way of illustrative example, if an individual wants to see their own performance review notes or payroll records, these are likely considered employee records handled as part of employment. Because of that, the employee record exemption usually applies, which means they may not be able to access the information under the Privacy Act and APP 12.

On the other hand, if an individual requests information that is not part of their employee record or isn’t directly related to their employment, such as CCTV footage of the office collected for general security, the employee record exemption may not apply, and an individual may be entitled to access it under APP 12 subject to any other relevant exceptions to access.

Is the employee records exemption too broad?

The Privacy Act Review Report, released by the Attorney-General’s Department in February 2023, directly addressed concerns about the breadth of the employee records exemption. Proposal 7.1 recommended that enhanced privacy protections be extended to private sector employees with the aim of:

- providing enhanced transparency to employees in relation to their personal and sensitive information;

- ensuring employers have adequate flexibility to collect, use and disclose employees’ information where reasonably necessary in the employment relationship;

- ensuring employees’ personal information is protected from misuse, loss and unauthorised disclosure, and destroyed where no longer required; and

- notifying employees and the Information Commission of data breaches likely to result in serious harm.

The Government’s response, published on 28 September 2023, agreed in principle that further consultation should be undertaken in relation to this proposal, including as to how privacy and workplace relation laws should interact. As of the date of this article, public consultation on this issue is expected but has not yet commenced.

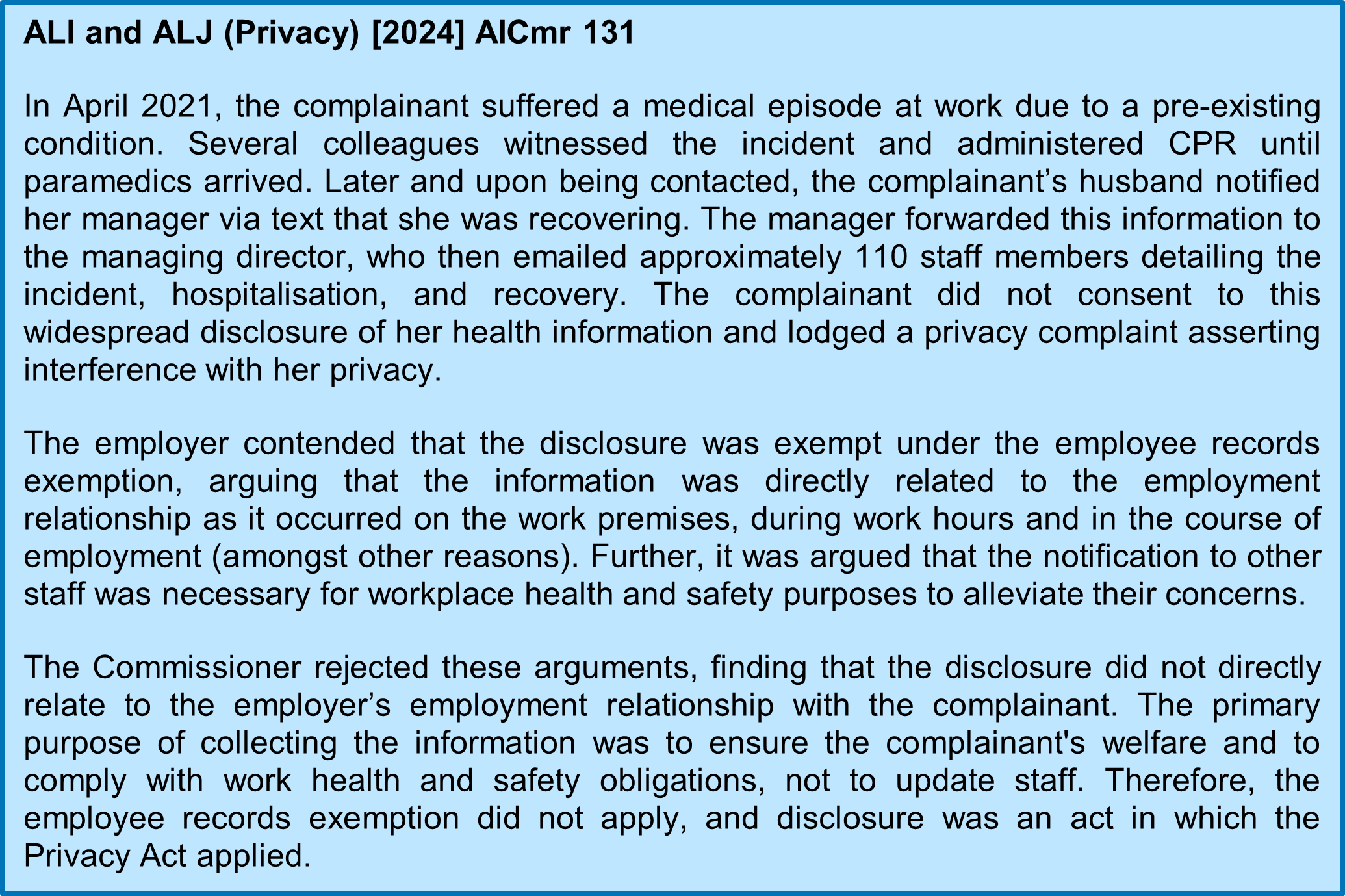

In any event, a recent determination from the OAIC suggests employers should not assume the employee records exemption will apply. The determination took a narrow view of the applicability of the exemption, suggesting that an act or practice should have an ‘absolute, exact or precise connection’ to the employment relationship to fall under the exemption.[7]

The bottom line?

Employees cannot always rely on the Privacy Act to obtain access to personal information held in employee records. The employee records exemption remains broad, but its application and interpretation is subject to why the information was collected and how it is used.

However, on the flip-side, employers cannot always rely upon the exemption to refuse access, or to not comply with collection processes for personal information or the data breach requirements if employee records are compromised. Organisations should also consider what their policies say about access, use and disclosure of employee records, as their policies may have gone further than what the law requires.

While the Privacy Act limits access to certain employee records, this is the reflection of parliamentary intention, and is further addressed by workplace laws. Part two of this series will examine access rights under the Fair Work Act, including which employment records must be kept, the enforceable right of employees and former employees to inspect and copy those records and some recent decisions illustrating the consequences of non-compliance.

---

[1] Privacy Act, section 6(1).

[2] Privacy Act, section 6C.

[3] Privacy Act, section 6D(4)

[4] Privacy Act, section 7B(3).

[5] Privacy Act, section 6(1)

[6] Explanatory Memorandum, Privacy Amendment (Private Sector) Bill 2000.

[7] ALI and ALJ (Privacy) [2024] AICmr 131 (20 June 2024), 42.

This article was written by Ariel Bastian, Senior Associate Corporate Commercial and Anna Kosterich, Lawyer Corporate Commercial.