Moral rights, misleading conduct and the battle for film credits: McCallum v Projector Films Pty Ltd

12 Nov 2025

The Federal Court decision in McCallum v Projector Films Pty Ltd [2025] FCA 903 (McCallum v Projector Films) has put the spotlight on an often-overlooked and rarely litigated corner of copyright law: directors’ moral rights in cinematographic works.

In McCallum v Projector Films, Justice Shariff granted an urgent injunction to stop the screening of a documentary at the Melbourne International Film Festival, not because of what the film showed, but because of who was (and wasn’t) credited on screen.

Background

The dispute concerned the feature documentary Never Get Busted!, centred on a Texas narcotics officer turned whistle-blower. Stephen McCallum had been engaged under contract as the film’s Principal Director.

Yet the production company, Projector Films, and co-respondent David Ngo promoted and exhibited the film with credits naming Ngo as the sole “Director”, diminishing or even omitting McCallum’s role, including at high-profile screenings such as Sundance and Dances With Films Festival.

McCallum applied to the Federal Court seeking to enforce his contractual and statutory rights to be credited, alleging:

- infringement of his moral rights under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth);

- misleading conduct under the Australian Consumer Law; and

- breach of the contract between McCallum and Projector Films.

Issues before the Court

Why did it matter? In the entertainment industry being the credited “Principal Director” can make or break a person’s career.

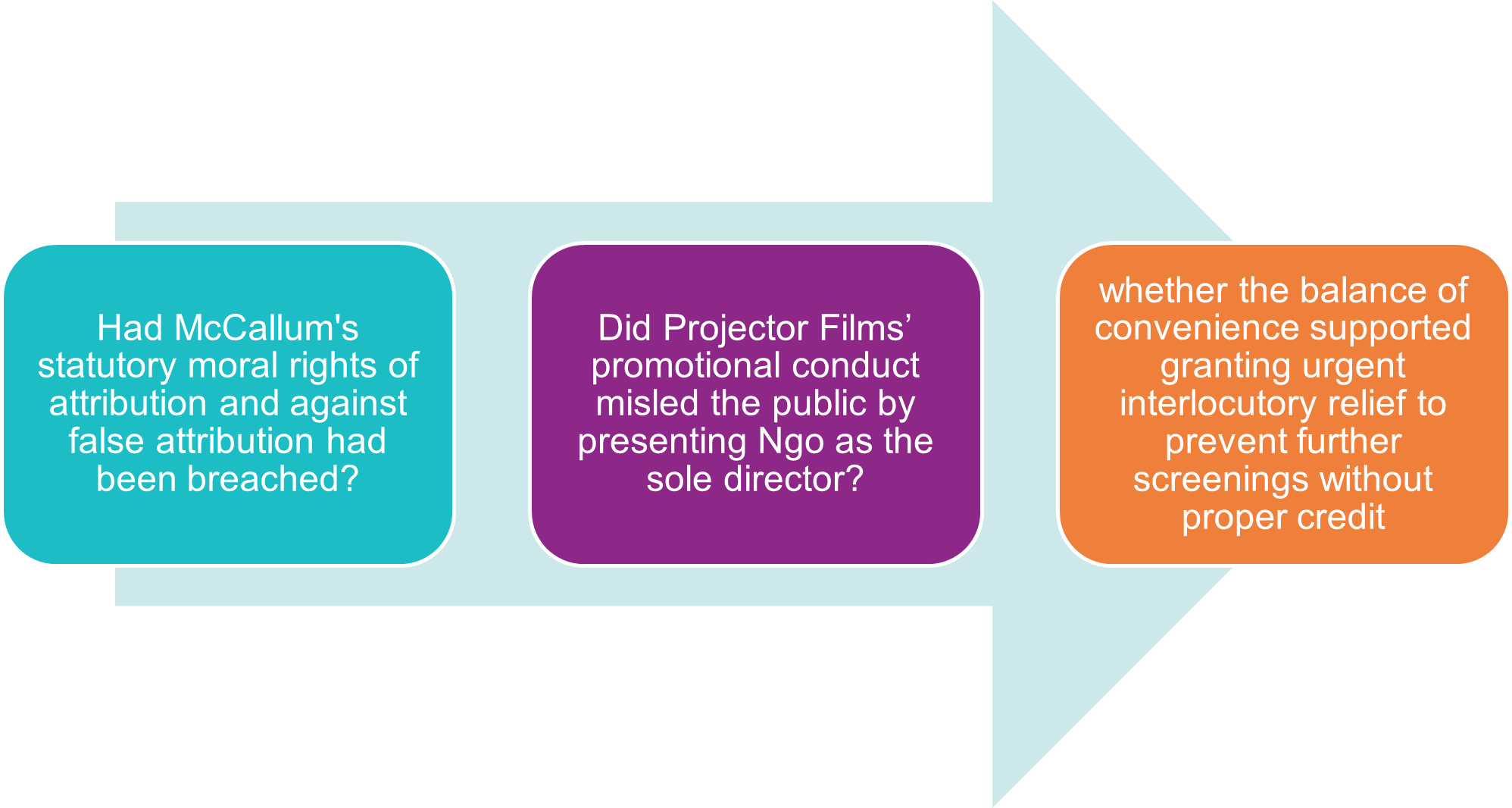

The Court was asked to consider 3 questions:

Central to McCallum’s argument: The Copyright Act makes clear that where a film has multiple directors, the “Principal Director” is the author for attribution purposes.

So what is attribution? Attribution essentially means giving credit where credit is due and properly acknowledging the creator of a work. False attribution is where another person (other than the creator) is falsely represented as the author or creator of that work.

Moral Rights in Film

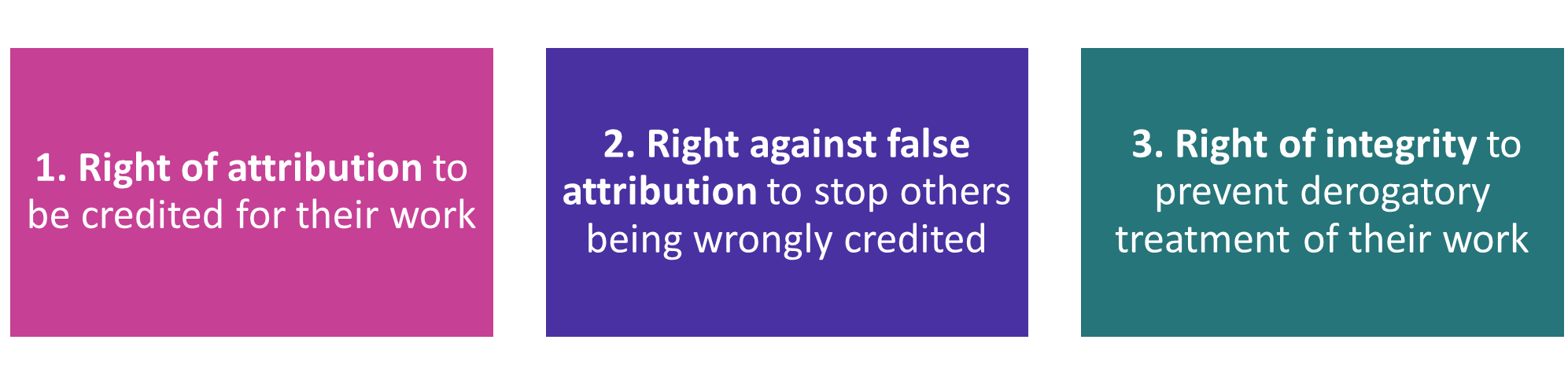

Australia’s copyright regime gives authors (including film directors) three key moral rights:

A Question of Consent

The production company argued that McCallum had waived his moral rights through a clause in the Director’s Agreement.

But there was a catch: under the Copyright Act, any consent to infringement must be express and in writing. Justice Shariff wasn’t convinced that the contractual waiver ticked those boxes. At least at this early stage, McCallum had a strong enough case to justify pressing pause on the film’s screenings.

The Court’s Call

Justice Shariff weighed the usual interlocutory injunction tests:

- Serious question to be tried? Yes – the claim was credible and raised novel issues about moral rights in film.

- Balance of convenience? Tilted in McCallum’s favour – lasting reputational damage from being side-lined as Principal Director outweighed any commercial inconvenience to the production company.

On 6 August 25, Justice Shariff granted interim injunctions restraining further screenings or promotions of the film unless:

- it credited McCallum alone and included the credit line “Directed by Stephen McCallum”; or

- promotional material gave him proper attribution as Principal Director.

An alternative suggestion – to show the credits with a disclaimer that they were “subject to court proceedings” – was dismissed as commercially toxic.

Why does it matter?

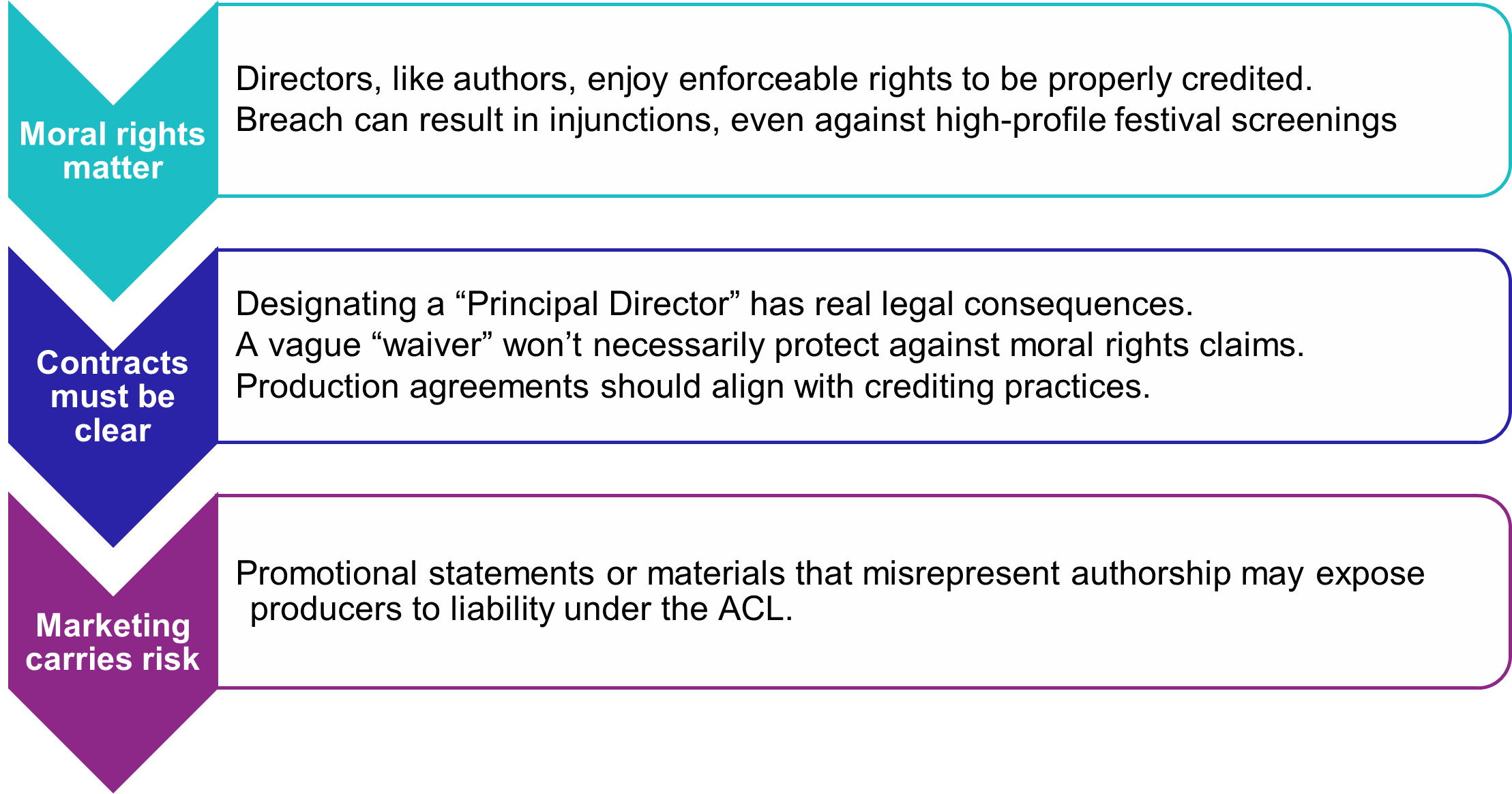

This case is already turning heads across the creative industries. A few key lessons stand out:

Where to from here?

This case was just the opening act. The matter returned to the Court for a full trial in September where the Federal Court was set to more closely examine the scope of directors’ moral rights in Australia. The final judgement from this trial is yet to be publicly published.

Regardless of the outcome of the trial, this case has already set the stage for a broader industry conversation about how contracts, credits and creators’ rights intersect in the digital era. The interim orders in this case already demonstrate the Court’s willingness to protect directors’ reputational interests swiftly and decisively.

This article was written by Nisali Pallewela, Restricted Practitioner Corporate Commercial. For specific legal advice please contact Elizabeth Tylich or Ariel Bastian.