Big brother in the hardware aisle: Bunnings oversteps privacy rights by using CCTV to collect “faceprints”

16 Nov 2025

What happens when a household name crosses the line on privacy? On 29 October 2024, the Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) determined that Bunnings Group Limited breached the Privacy Act 1988 (Cth) and the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs) by using facial recognition technology (FRT) to collect customers’ personal and sensitive information across 63 stores in Victoria and New South Wales between 2018 and 2021.

This determination reinforces that convenience, security, or loss prevention objectives cannot justify privacy-invasive technologies deployed without robust consent, notice, and proportionality measures.

How the system worked and why the data was sensitive

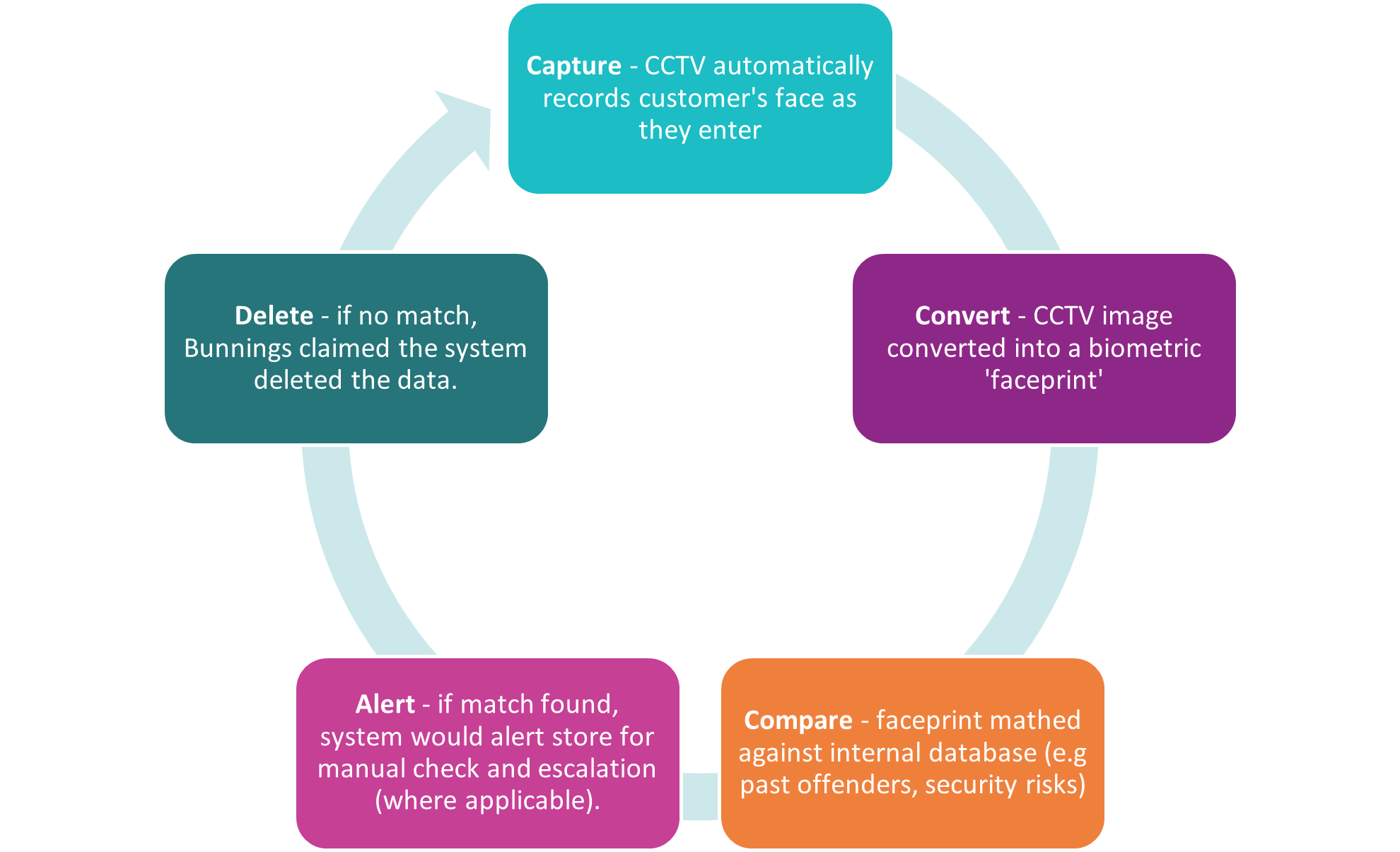

The FRT system operated by Bunnings’ followed a continuous cycle, automatically scanning and processing every customer who entered their FRT enabled stores as follows.

Ultimately, this meant that every shopper over three years was scanned, whether or not they were suspected of wrongdoing.

It is critical to note that facial recognition data, such as the ‘faceprints’ collected by Bunnings, qualifies as sensitive information under the Privacy Act. This is because the data captures biometric identifiers – being unique physical traits that can identify an individual.

The APPs impose stricter conditions on handling such data. Unless a specific exception applies, organisations can only collect sensitive information if:

- an individual has provided informed consent; and

- the collection is reasonably necessary for one or more of the organisation’s legitimate functions or activities.

This was a critical factor in this determination. The sensitive nature of the faceprints elevated the privacy risk, making any compliance failures far more serious than if ordinary customer information such as email addresses was being collected.

OAIC finding: balancing privacy and security

The OAIC investigated and determined that Bunnings breached several APPs by:

- collecting sensitive information (facial images and biometric templates) without consent;[1]

- failing to notify individuals about the facts, circumstances and purposes of collection;[2] and

- not having sufficient internal systems and policies to ensure ongoing APP compliance.[3]

Bunnings argued that their use of FRT was for safety and crime prevention, arguing the system was ‘reasonable and necessary’ for protecting customers and staff. However, the OAIC found the system was neither proportionate nor necessary to achieve its purpose.

Whilst the OAIC considered that the system was perhaps the most efficient and cost-effective option and provided a sense of comfort to staff, scanning every customer was the most privacy intrusive optionavailable. This combined with inadequate notification to individuals about the use of the system, meant the OAIC found the benefits did not outweigh the privacy risks it imposed.

The OAIC directed Bunnings to publish a public statement acknowledging the breaches and to retain relevant data only for 12 months before destroying it. Bunnings is currently appealing the outcome.

“Reasonable Steps” means more than policy documents

Many of the APPs require organisations to “take such steps as are reasonable in the circumstances” to protect personal information. As a context-based principle, it follows that the more sensitive the data or the greater the potential harm, the more robust the steps need to be.

In the context of emerging technologies, this obviously goes beyond simply having a privacy policy in place. The Bunnings determination signals to organisations the necessity of integrating privacy considerations (including systems, procedures, and training) at every stage of adopting such technologies. Technologies found to be privacy-invasive cannot be justified on efficiency or security grounds alone.

In the context of technology such as FRT, this means:

- undertaking a Privacy Impact Assessment before deployment;

- securing valid, informed consent, especially when handling sensitive biometric information;

- providing clear and accessible notices of data collection when it is collected;

- limiting data collection to what is necessary for a clearly defined purpose; and

- regularly reviewing and auditing data practices and third-party vendor arrangements.

Broader message for businesses

While the OAIC’s findings relate specifically to facial recognition, the reasoning applies to any technology that gathers personal or sensitive information, including AI systems, behavioural tracking tools or data analytics platforms.

For boards and compliance teams, this decision highlights the need to:

- embed privacy governance into technology risk management frameworks;

- revisit data retention and deletion practices;

- map all data flows, including where information is stored temporarily; and

- educate staff on handling sensitive data, especially where technology vendors are involved.

The OAIC’s finding against Bunnings sends a clear signal that even well-intentioned uses of emerging technology need to be handled with care, and with privacy considerations front of mind. This is critical in both reducing regulatory risk and strengthening consumer trust.

---

[1] APP 3.3.

[2] APPs 5.1 and 5.2.

[3] APPs 1.2 and 1.3.

This article was written by Ariel Bastian, Senior Associate Corporate Commercial, Karen Fong, Associate Corporate Commercial and Tegan Hill, Restricted Practitioner Corporate Commercial